- Banking

- Wealth

- Privileges

- NRI Banking

- Treasures Private Client

- Global food prices have joined energy in registering sharp gains

- … This marks a double whammy for households

- We explore whether higher global food indices mean higher local food inflation and…

- ...whether core inflation typically catch up with headline inflation or vice-versa

- Regional policymakers face a difficult decision on the timing and pace of policy normalisation

Related Insights

- Digital Assets 2Q24 Update webinar: Tuesday May 14th, 4pm SGT 26 Apr 2024

- Research Library26 Apr 2024

- China chartbook: 2Q24 GDP growth tracking 5%25 Apr 2024

Below is a summary; for the detailed and full report, please download the PDF

Overview

Halfway through the year, commodities face a tug-of-war – supply disruptions triggered by geopolitical tensions and reopening boost to demand stoking prices, whilst concerns over an impending growth slowdown due to policy normalisation and quantitative tightening check optimism.

Global food prices joined energy in registering sharp gains this year. For instance, the IMF commodity indices for food & beverages, as well as non-fuel indices, have risen sharply this year, to record levels. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (UN FAO) food index touched a record high in April and levelled off in May but was still up by 26% yoy on average in the two months. While the lift is broad-based amongst sub-segments, vegetable oil led by a wide margin, followed by cereals.

High food and fuel prices mark a double whammy for households as consumers tend to spend a higher proportion of their incomes on basic necessities. The weight of food in the ASEAN-6 consumer price inflation basket is significant at 20-40%, which together with fuel, accounts for at least 50-60% of the basket.

We examined ASEAN countries’ inflation dynamics and the impact of high energy costs/ geopolitics in ASEAN-6: Assessing the impact of oil and geopolitics and ASEAN-5: Evaluating key inflation drivers, besides exploring reopening dynamics in ASEAN-6: Transiting to an endemic state.

In this note, we assess three aspects:

- Do gains in these international food indices imply higher regional food inflation

- In the midst of worries over second-round effects from higher food plus fuel, we assess if core inflation typically catches up with headline CPI inflation, or vice-versa

- Discuss the specific dynamics of each of the ASEAN-6 countries

International food prices trend vs regional inflation

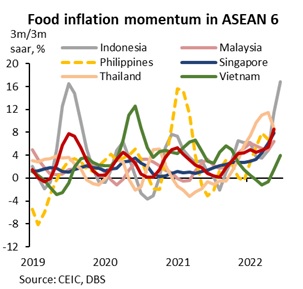

High food prices pose a crucial policy challenge for policymakers, as supply-side inflation in basic necessities such as food and fuel tends to alter inflation perception, i.e., the longer it lasts, the higher the potential second-order impact and spillover onto wage growth. Our momentum gauge i.e., 3m/3m saar % for the region’s food inflation is rising (see chart).

The latest bout of increase in food prices is driven by: i) supply distortions due to geopolitical tensions and inclement weather /and restrictive trade policies by major exporting countries; ii) pass-through of higher energy prices, feeding into transportation and food costs.

Under i) amidst inflationary concerns globally and food security assuming priority, several countries have taken restrictive measures to ensure sufficient domestic stockpiles to help contain prices and lower hardship amongst the populace.

Globally, since the Ukraine crisis, about 16.9% of the share of global trade (by calories) had faced some extent of food export restrictions, more than the post-first wave of Covid as well as the 2007-08 crisis. In the latest update, the share stands at 12.5%. Since Mar-20, about 18 countries have imposed an actual ban, whilst seven have imposed export licensing (see chart in PDF), according to data from International Food Policy Research Institute.

This includes a ban on wheat exports by India, a temporary ban by Indonesia on palm oil (lifted since then), Malaysia (chicken, partly eased), etc. Additionally, Russia and Ukraine are crucial suppliers of wheat, corn, fertiliser, and feedstock, supplies of which have been disrupted due to the ongoing military conflict. The vulnerability of the food production structure is high as it is relatively less diversified and more concentrated, especially in commonly used staple varieties, which was reinforced by the fallout of the Russia-Ukraine military conflict.

On ii) high oil prices are also likely to have a pass-through impact on food segments. The correlation of changes in Brent prices (yoy) to the UN FAO food index (yoy) in the past decade is significant at 0.77. Brent prices were up by more than 50% in 2021, followed by another 48% jump in 2022 year-to-date (ytd), which is likely to have fed through to higher production costs for agriculturists, transportation (affecting wholesale/ retail prices), and other relevant industries including petrochemicals, etc. Concurrently, prices of fertilisers, which make about a sixth of agricultural costs, too have translated into higher input costs.

Do gains in global food price indices imply higher regional food inflation?

The UN FAO food index touched a record high this year, up by an average of 25% yoy ytd. Other indicators from the UN, IMF, and World Bank tracking global food price trends have registered similar steep increases.

While these portend pipeline inflationary risks, our calculations show that the correlation between international food price indices (yoy) and ASEAN-6 food inflation (yoy) (on a contemporaneous basis, using monthly data from 2017 to May-22) is surprisingly weak, suggesting the transmission mechanism is not one on one, on to regional inflation. A working paper by UN FAO highlighted key domestic forces that can mitigate or aggravate the spillover impact of moves in the global food commodities. Key amongst which were:

- Commodity imports, i.e., economies that are net food importers, tend to face higher costs if global costs rise. A study on agri-food export competitiveness of ASEAN countries in 2020 highlighted that the Philippines and Singapore run net trade deficits, whilst the remaining have positive trade balances, the highest amongst which is Thailand. Countries that are net food importers are price takers and experience the spillovers from high global prices;

- Market power and policy interventions: The extent to which shocks in international markets are transmitted to final consumers hinges on the ability of businesses to pass on additional costs. This capacity is also influenced by countervailing action by the respective governments. Policy interventions (tariffs, input subsidies, etc.) affect the degree of correlation between international market prices and domestic prices. On the latter, restrictive policies like temporary bans (Indonesia on palm oil, India on wheat/ sugar, etc.) on exports of certain food segments to safeguard domestic consumers tend to distort the pass-through impact.

In all, whilst a rally in global food commodity price indices is a source of worry, the pass-through to final domestic prices is asymmetric depending on the countries’ dependency on imports as well as the extent of price controls domestically.

In this regard, Singapore and the Philippines are likely to be impacted the most by movements in global food indices, whilst Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia are less impacted.

Headline vs core inflation dynamics – via a regression study

We assess the dynamics of headline vis-à-vis core inflation across the ASEAN-6 economies that would be relevant for monetary policy decisions. Specifically, we carry out regressions to analyse if

- headline inflation in the ASEAN-6 countries, historically, reverted to the core gauge or

- core returned to the headline (see Appendix: Methodology at the end of the PDF for details and charts).

The results seek to shed light on whether shocks beyond that measured in core had resulted in signs of persistency in headline inflation and/or broadening to core inflation, from a statistical perspective. This could provide a good barometer to policymakers on whether to pre-empt with policy tightening measures or bide time.

Based on our regression analysis using two time periods (Jan-16 to May-21 and Jan-16 to May-22 to include price developments over the past year), we make the following observations:

- In part 1 of the analysis, headline inflation has tended to revert to core inflation across ASEAN-6, using data from Jan-16 to May-21. This suggests that in most cases, supply shocks-induced pick-up in inflation did not necessarily translate into generalised core pressures. We suspect that this limited pass-through reflects the fragmented nature of labour markets in the ASEAN-6 countries (except Singapore) where the dominance of informal sector carries limited bargaining power on wages. ILO data shows that the share of the informal employment is in the range of 60-80% in the region.

- Extending the data to May-22 lowered the speed of headline to core reversion for Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, as commodity movements continue to develop as we write. Thailand saw a noticeable decline, capturing the strong headline inflation take-off in 2022. For Singapore, it suggested no reversion to core, reflecting the underlying concern over the rapid pick-up in headline price pressures over the past year and that it could induce wage-led price pressures.

- The other part of the study, i.e., whether core readings revert to the headline, also holds interesting takeaways. Core inflation did not show signs of reversion to headline inflation, and there was a little broadening of price pressures, using data from Jan-16 to May-21. Indonesia was an exception. The divergence may reflect of the energy subsidies in place for years (we discuss this here), which has essentially seen the headline and core readings move largely in sync.

- Extending the study to May-22 had little impact on the results, except for Singapore, where the coefficients point to core’s reversion to the headline. This likely reflects the sharp pick-up in Singapore’s core inflation that prompted the authorities to adopt three tightening moves since October 2021. In contrast, muted demand-pull inflation in the early part of 2022 due to a fragile growth recovery prompted other policymakers to tighten policy gradually in 1H. We expect more to join the hawkish bandwagon in 2H as besides high inflation, financial market stability (see chart in PDF) also becomes a priority for the respective central banks.

In the PDF, we discuss each of the ASEAN-6 countries.

To read the full report, click here to Download the PDF.

Subscribe here to receive our economics & macro strategy materials.

To unsubscribe, please click here.

Topic

The information herein is published by DBS Bank Ltd and/or DBS Bank (Hong Kong) Limited (each and/or collectively, the “Company”). This report is intended for “Accredited Investors” and “Institutional Investors” (defined under the Financial Advisers Act and Securities and Futures Act of Singapore, and their subsidiary legislation), as well as “Professional Investors” (defined under the Securities and Futures Ordinance of Hong Kong) only. It is based on information obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but the Company does not make any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy, completeness, timeliness or correctness for any particular purpose. Opinions expressed are subject to change without notice. This research is prepared for general circulation. Any recommendation contained herein does not have regard to the specific investment objectives, financial situation and the particular needs of any specific addressee. The information herein is published for the information of addressees only and is not to be taken in substitution for the exercise of judgement by addressees, who should obtain separate legal or financial advice. The Company, or any of its related companies or any individuals connected with the group accepts no liability for any direct, special, indirect, consequential, incidental damages or any other loss or damages of any kind arising from any use of the information herein (including any error, omission or misstatement herein, negligent or otherwise) or further communication thereof, even if the Company or any other person has been advised of the possibility thereof. The information herein is not to be construed as an offer or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities, futures, options or other financial instruments or to provide any investment advice or services. The Company and its associates, their directors, officers and/or employees may have positions or other interests in, and may effect transactions in securities mentioned herein and may also perform or seek to perform broking, investment banking and other banking or financial services for these companies. The information herein is not directed to, or intended for distribution to or use by, any person or entity that is a citizen or resident of or located in any locality, state, country, or other jurisdiction (including but not limited to citizens or residents of the United States of America) where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation. The information is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any security in any jurisdiction (including but not limited to the United States of America) where such an offer or solicitation would be contrary to law or regulation.

This report is distributed in Singapore by DBS Bank Ltd (Company Regn. No. 196800306E) which is Exempt Financial Advisers as defined in the Financial Advisers Act and regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. DBS Bank Ltd may distribute reports produced by its respective foreign entities, affiliates or other foreign research houses pursuant to an arrangement under Regulation 32C of the Financial Advisers Regulations. Singapore recipients should contact DBS Bank Ltd at 65-6878-8888 for matters arising from, or in connection with the report.

DBS Bank Ltd., 12 Marina Boulevard, Marina Bay Financial Centre Tower 3, Singapore 018982. Tel: 65-6878-8888. Company Registration No. 196800306E.

DBS Bank Ltd., Hong Kong Branch, a company incorporated in Singapore with limited liability. 18th Floor, The Center, 99 Queen’s Road Central, Central, Hong Kong SAR.

DBS Bank (Hong Kong) Limited, a company incorporated in Hong Kong with limited liability. 13th Floor One Island East, 18 Westlands Road, Quarry Bay, Hong Kong SAR

Virtual currencies are highly speculative digital "virtual commodities", and are not currencies. It is not a financial product approved by the Taiwan Financial Supervisory Commission, and the safeguards of the existing investor protection regime does not apply. The prices of virtual currencies may fluctuate greatly, and the investment risk is high. Before engaging in such transactions, the investor should carefully assess the risks, and seek its own independent advice.

Related Insights

- Digital Assets 2Q24 Update webinar: Tuesday May 14th, 4pm SGT 26 Apr 2024

- Research Library26 Apr 2024

- China chartbook: 2Q24 GDP growth tracking 5%25 Apr 2024

Related Insights

- Digital Assets 2Q24 Update webinar: Tuesday May 14th, 4pm SGT 26 Apr 2024

- Research Library26 Apr 2024

- China chartbook: 2Q24 GDP growth tracking 5%25 Apr 2024