As the statesman that first normalised relationships between China and the US, Henry Kissinger paved the way for China to rejoin the international theatre, changing geopolitics – and the global economy forever. Boasting a deep understanding of Chinese culture and history, Kissinger once noted that Western strategic thinking, like chess, focused on the “centre of gravity”, or decisive victories. On the other hand, the Chinese approach is closer to the game of wei qi, which “teaches the art of strategic encirclement”, stressing relative advantage on multiple fronts and taking a holistic approach. Given the complexity of supply chains and the volatile geopolitical environment today, Kissinger’s observation has never been more relevant as diversification strategies rise to the top of business considerations. In particular (and fittingly enough), a China+1 strategy is gaining traction not just among foreign companies that base manufacturing in China, but more glaringly, Chinese companies themselves.

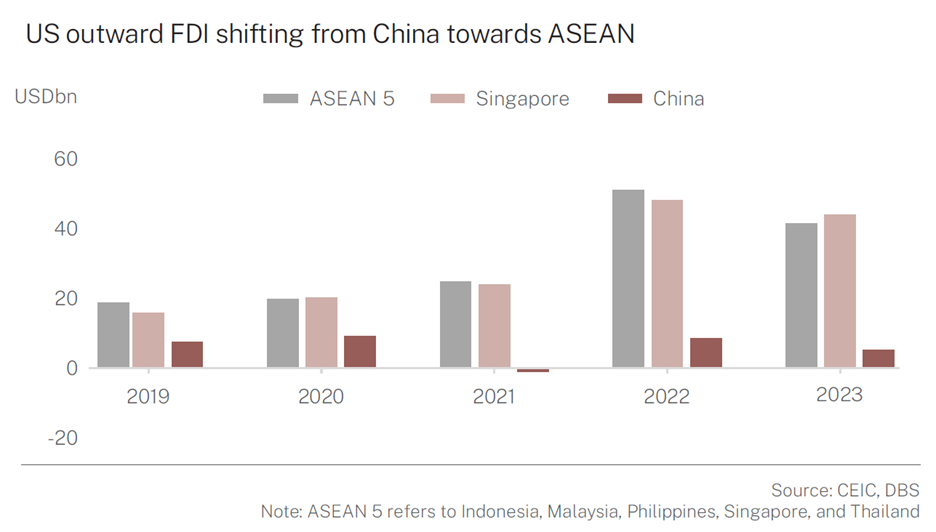

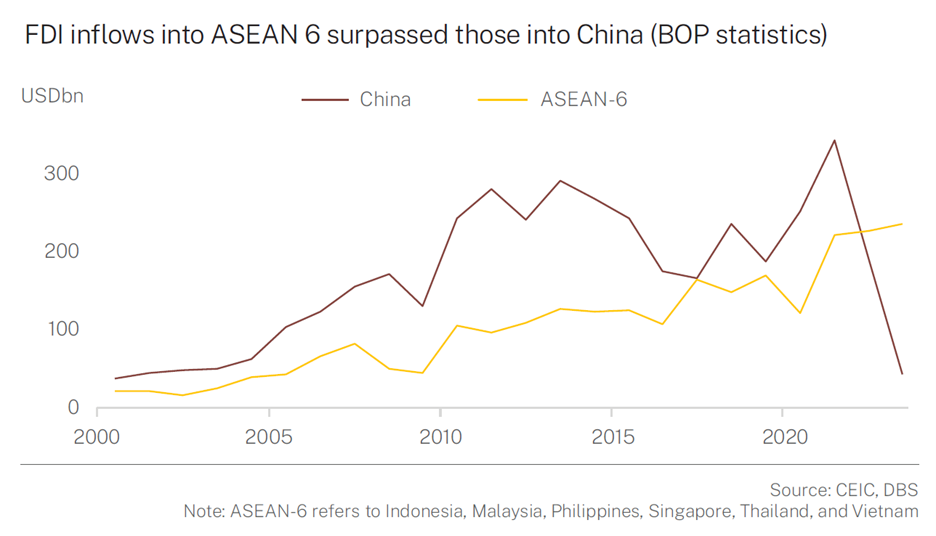

This is due to two reasons: to mitigate the risks of over-concentration on a single market; and to capitalise on global growth prospects and opportunities, especially as China’s economy matures while costs rise. FDI inflows into ASEAN 6 – Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam – exceeded those into China consecutively for 2022 and 2023, suggesting that businesses and investors are diverting some resources into the region. An interplay of factors including geopolitical tensions, rising costs, and a maturing economy explains the decline in FDI inflows into the country. Singapore, in particular, has become an attractive channel of diversification for US investment, capturing over 90% of US ASEAN 6 inflows in the past five years. Across ASEAN countries there are generally no restrictions on foreign investment apart from select critical industries such as financial services, telecommunications, and media.

Geography shapes destiny

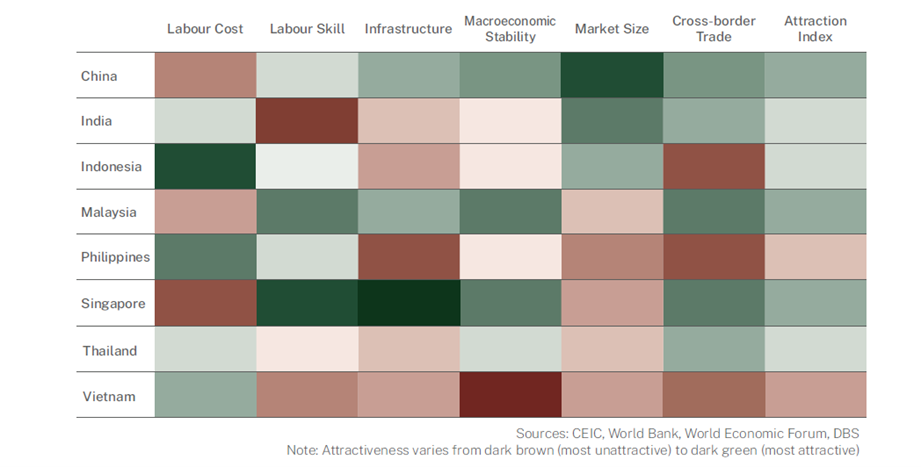

For businesses looking to diversify supply chains, the cost competitiveness of each country is paramount, besides the advantage of close geographical proximity to China. Labour costs differ dramatically across different countries. The average monthly salary in Singapore is USD4,900, for instance, which is substantially higher than China at USD1,400 and Malaysia at USD800.

Logically, it is ideal to mass-produce lower value products in developing countries with lower cost structures. On the other hand, high-tech and low-volume products are preferredly manufactured in developed nations such as Japan, South Korea, and Singapore due to their robust infrastructure, stable governance, and skilled workforce.

Businesses looking to expand beyond China should prioritise growth and demand when evaluating potential markets. Emerging markets in Southeast Asia such as Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar boast vast populations of new consumers, presenting untapped avenues for growth. Meanwhile, rapidly growing countries like India, Indonesia, and Vietnam showcase youthful demographics and a burgeoning middle class, buttressing both the labour force and consumer base.

For more sophisticated markets with established capital markets, investors can consider Europe and the US. Both offer stable consumer demand, advanced technology, intellectual property and skilled workforces. The US has a massive consumer market with higher per capita income and consumer spending, while Europe provides access to a large integrated market with high purchasing power. Both regions offer comprehensive government incentives and sophisticated capital markets for fund raising.

Within ASEAN, Singapore stands out as a competitive FDI destination thanks to its world-class manufacturing ecosystem, skilled talent pool, and excellent connectivity. While Singapore’s domestic market is small and labour costs are relatively higher, it benefits from higher labour productivity and comprehensive trade agreements for exports. Malaysia is also an attractive location for FDI, offering a strategic location with relatively skilled labour and well developed infrastructure. Compared to Singapore, Malaysia could potentially be a more cost-effective choice for businesses given its relatively lower labour cost, while still benefitting from strong connectivity through cross-border trade.

One size does not fit all

Macroeconomic conditions aside, to decide on the most suitable location to operate in outside of China, businesses will also have to factor in the industry in which they operate, and whether they are looking to diversify their supply chains or seek inroads into new markets. Illustrated below are some industries that will benefit the most from the China+1 strategy.

Supply chain diversification: Semicon manufacturing, renewable energy, and metals

Semiconductor Manufacturing: Singapore has a well-developed semiconductor ecosystem with players across the value chain, ranging from the fabless (Marvell, Broadcom, MediaTek) to foundries (UMC, GlobalFoundries). Worthy contenders can also be found in integrated device manufacturers (Micron, Infineon), equipment makers (Applied Materials), as well as Taiwanese outsourced semiconductor assembly and test (OSAT) vendors (ASE, JCET). Other Chinese tech giants such as ByteDance, Alibaba (via Lazada) and Tencent have all set up regional offices in Singapore.

Despite its higher cost structure, Singapore’s mature ecosystem is well-suited for advanced manufacturing, which is capital-intensive but requires less labour. Singapore attracts higher-end OSAT vendors due to its capabilities in advanced packaging, which offers higher margins. Additionally, its political neutrality and business-friendly policies create a stable environment for long-term planning and investment. Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam have relatively lower cost-based structure compared with China. With their strong manufacturing base and improving infrastructure, Malaysia and Thailand have been attracting OSATs and downstream electronics manufacturing services operations. Meanwhile, Vietnam’s proximity to China offers a significant advantage, facilitating staff training and material sourcing from China.

Renewable Energy: China currently dominates the renewable energy supply chain, controlling over 80% of the global market share for polysilicon, wafers, and solar glass; and 65% of the global market share for wind equipment. This concentration poses risks, especially given the geopolitical tensions between China and the US. In addition, the Covid-19 pandemic and global conflicts have exposed the frailties of supply chains and the dangers of over-reliance on a single supplier.

To better secure supply chains, manufacturers are seeking new production bases outside China. Three key considerations include 1) no import restrictions on Chinese solar components, 2) cost efficiency with regards to electricity tariffs, wages, and subsidies, and 3) availability of skilled labour and established export logistics.

Southeast Asia emerges as a favored destination due to its proximity to China, favourable political environment, and abundant resources like land, labour, and ports. Saudi Arabia is another attractive hub, offering low energy costs, strong local demand, and proximity to European markets. Notable Chinese oil majors with a presence in Singapore include PetroChina, Sinopec, Huaneng Power and CNOOC, while other energy players like Longi and JinkoSolar have a presence in both Malaysia and Vietnam.

Metals & EV Batteries: Indonesia banned exports of nickel ore in 2014, the country built up its downstream industry, producing Class 2 nickel products such as ferronickel and nickel pig iron. Consequently, Indonesia’s contribution to the global supply of refined nickel is expected to surge to 46% in 2025, up from a mere 2.6% in 2015. This growth, coupled with Indonesia’s abundant nickel reserves, has attracted major EV and battery players like Tesla, CATL, and LG Energy Solution to establish battery plants in the country. The region’s competitive labour force, strong government support, and ample resources make Southeast Asia an attractive investment destination for the EV battery industry, which is crucial for renewable energy and net-zero goals. The top two ternary precursor (raw material for battery) suppliers in China, CNGR Advanced Material and GEM, are also expanding their presence in Indonesia.

Growth Prospects: Consumer Goods & Services, Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals

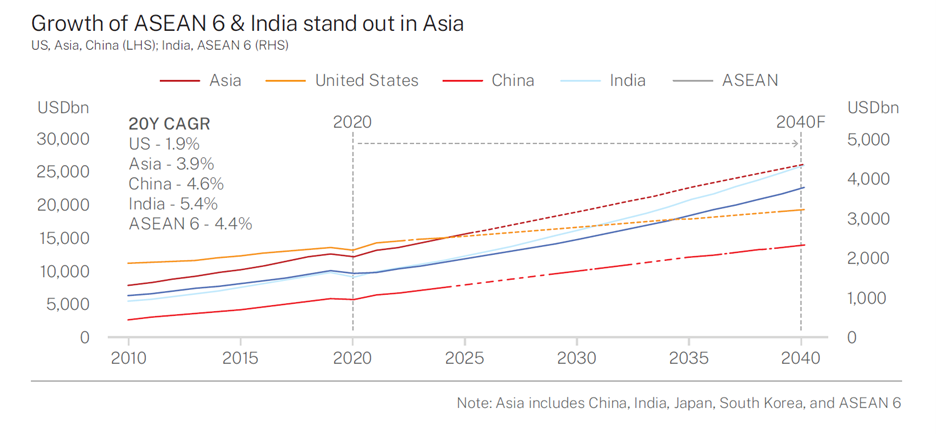

Consumer Goods & Services: The household consumption of ASEAN 6 and India will rise to USD5.1tn by 2030, around half of China’s expected household consumption in 2030. This growth is expected to outpace other Asian countries with a CAGR of 4.4% for ASEAN 6 and 5.4% for India, compared to 3.9% for the entire Asian region. Simply put, both regions are sizable and growing markets that represent a significant growth opportunity for companies in the consumer goods and consumer services space. Singapore, being culturally similar to China and offering favourable tax rates, is an ideal location for companies to establish hubs for managing distribution and finances within the ASEAN region.

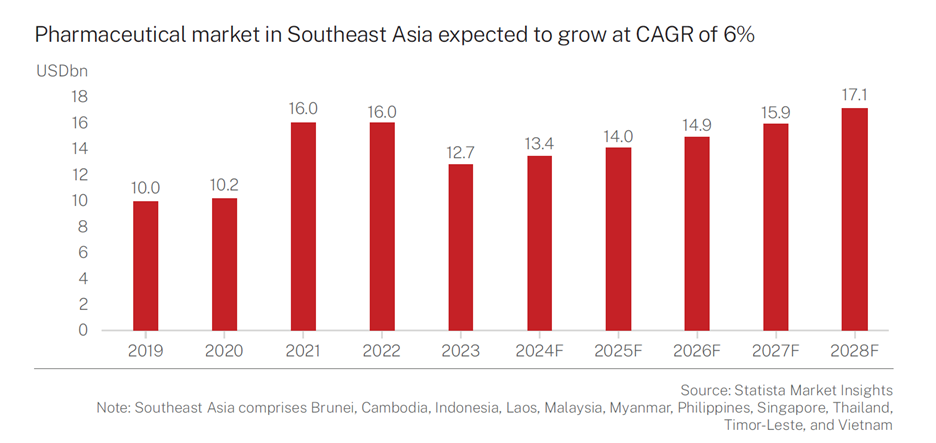

Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals:Like other businesses, drug and medical device makers are expanding beyond China and into ASEAN to diversify manufacturing and tap on the growth of ASEAN market. Southeast Asia’s pharmaceutical market is expected to grow at a 6% CAGR in 2023E-28F, according to Statista Market Insights. The main allure of Southeast Asia (ex-Singapore) is its relatively lower labour costs. Monthly wages in Indonesia, Vietnam, and Thailand are over 50% lower than that in China. This is a particularly important factor for the medical devices manufacturing industry, which struggles with a higher staff-costs-to-sales ratio. Looking at Chinese companies – Modern Dental, a denture manufacturer established in Hong Kong, will double its manufacturing capacity in Vietnam in 2024.

Critical considerations

Supply chains today are far more intricate than they were in the past. Shifting manufacturing capacity beyond China requires more than simply purchasing factory buildings. Businesses must establish intricate and robust supply chains, ensuring access to raw materials and labour while adhering to local regulations and cultural nuances. Technology and semiconductor supply chains, for example, are notorious for their complexity as they involve a sprawling network of companies across countries.

While moving to lower-cost countries might seem like a cost-saving measure, it does not guarantee increased margins. Businesses face significant investments in land, infrastructure, and equipment, potentially leading to diminished economies of scale if manufacturing capacity is spread across multiple locations. In the long run, businesses have to evaluate if adopting a China+1 strategy will truly bring them cost savings, apart from the safety of diversifying their investments.

Given the increasingly advantageous environment for doing business in Southeast Asia, the China+1 approach is a good opportunity to alleviate excessive reliance on a particular market while allowing businesses to seize the potential for expansion on a global scale. This may seem counterintuitive, but during a time when deglobalisation is gaining traction, businesses and investors, which have long relied on China’s supply-chain dominance and immense market, can potentially look beyond China and explore the broader world.

DisclaimersJoin DBS Private Bank

With our size, safety and expertise, you can fully immerse yourself in life's best moments while we handle the rest.

It’s time to take the next step, the logical step.