breaking-new-ground

Breaking New GroundStock exchange agent: How DBS helped catalyse change in Singapore’s IPO market

By DBS and The Nutgraf, 2 Aug 2023

Mr Tan Soo Nan sharing his paper on “The Singapore Stock Market” at a conference in London in 1986. Photo: DBS

The articles in this series are presented jointly by DBS and content agency The Nutgraf. In the lead up to the bank’s 55th anniversary, The Nutgraf team interviewed 12 alumni to uncover these lesser-known stories about the bank in its early days, and its key contributions to a young and developing Singapore.

Early one morning in June 1978, an unexpected phone call conveying an important message from then-Deputy Prime Minister Goh Keng Swee jolted Mr Tan Soo Nan and his team out of their drowsy state.

The night before, the DBS team had just completed a massive subscription exercise for the initial public offering (IPO) of Singapore Bus Service (SBS), which would mark a key milestone in developing the nation’s young stock market.

It was “a memorable project because it was the first time that we had to work with the Central Provident Fund (CPF), and the Government, to put together a scheme that allows Singaporeans to draw on the CPF to invest in listed securities”, recalled Mr Tan, who worked at DBS from 1971 to 2000 in various key roles including as the bank’s senior managing director.

The SBS issue was a huge success, said Mr Tan. “The subscription was overwhelming. That was the easy part.”

But Dr Goh had another plan, one which was laced with a tinge of socialism. Instead of simply treating the IPO as a market-led fund-raising exercise, Dr Goh wanted the exercise to cater to social needs as well.

The Deputy Prime Minister felt strongly that the shares of SBS, a public bus transport company, should be allocated only to applicants who did not own cars.

“The rationale was: these people take public transport. If they use their CPF money to buy SBS shares and SBS makes money, dividends would be paid to them. And that would, in a way, cover some of their transport costs,” explained Mr Tan.

This thinking – to enlarge the base of share-owning Singaporeans while spreading the nation’s wealth in equitable ways to a broader swathe of the population – would guide some of the mega IPOs DBS handled over the years, such as Jurong Shipyard and SingTel.

DBS also sought to help advance the young Stock Exchange of Singapore (SES) in line with the vision of then-Finance Minister Hon Sui Sen, who stated in 1973 that the Exchange should “increasingly perform the function of mobilising capital resources not only for Singapore, or for Southeast Asia, but also for the whole of the Asia Pacific Basin”.

Over the years, DBS would help create IPO milestones like the 1985 listing of Singapore Airlines, which was the first international IPO of a local firm, as well as the first foreign listings from Japan, China, Hong Kong and other markets.

Got car, no shares

For Mr Tan, who participated in many key capital market transactions during his 29-year DBS career, one of the most memorable is still the SBS IPO.

Besides its significance as the first IPO where CPF funds could be used, the “out of the blue” call after the subscription closed also left a deep impression, said Mr Tan.

Dr Goh’s instructions were clear and simple, “All those who own cars, no shares.”

“Luckily for us, there was a provision in the IPO prospectus that said that as the lead manager, we can impose any terms and condition. Therefore, legally, we were covered,” recounted Mr Tan.

The team had to check against the Registry of Vehicles (ROV)’s database of car owners in batches of 1,000, systematically taking out the names of those applicants who owned cars and putting them on a reserved list.

“This process of going back and forth eventually allowed us to do the complete allocation of shares to those who did not own a car,” said Mr Tan.

The sudden change in conditions was also another challenge. A misstep could result in DBS facing a horde of angry investors. But clear communication through the right channels achieved the desired outcome.

Said Mr Tan, “We informed the press and the public about the new conditions and how we were going to do it. The results were delayed slightly, but it worked out. It’s a question of managing expectations.”

The listing craze

Singapore’s stock market embarked on a golden age in the 1980s, which saw some of today’s largest companies list during that period. This included Jurong Shipyard, which was later renamed Sembcorp Marine and is known as Seatrium today.

To allow for more Singaporeans to participate in the share offer, DBS set the balloting ratio to favour small investors who had applied for up to 9,000 shares. Even then, the IPO in August 1987 drew nearly SGD 10 billion in application monies from nearly 320,000 applicants who subscribed 145.7 times the number of shares offered. It was pronounced by the Straits Times as a “big hit”.

For DBS veteran Kan Shik Lum, who was dropped into the deep end as a young banker handling the Jurong Shipyard IPO, the transaction was “more like a nightmare”.

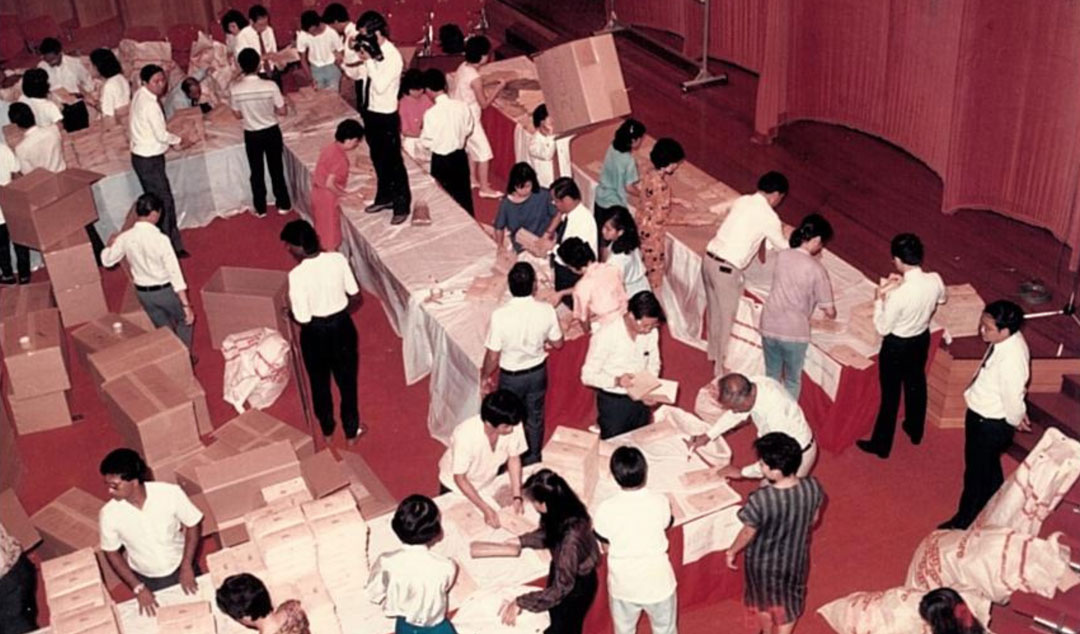

DBS employees sorting out and organising the application forms received for one of the IPOs in 1987. Photo: Mr Loh Soo Eng

The DBS team had to grapple with huge logistical and crowd control challenges as they manually processed hundreds of thousands of application forms and cashier’s orders for the subscription.

“The applicants formed a queue around the old DBS Building at 6 Shenton Way. There were even Malaysians coming down in Malaysian cars, trying to get hold of forms so that they could also stag and punt,” said Mr Kan.

Nearly all the meeting rooms in the DBS building were soon filled with mountains of paper forms, as harried staff first carried out the ballot, allocated shares, and then signed refund cheques for the balance of shares not allocated to applicants until their “hands almost dropped off”.

But the experience gained set the bank up to start leading some of the mega IPOs. In 1985, DBS became the first Singapore bank to be appointed as a lead manager of an international consortium – which included big names like Goldman Sachs, SG Warburg and Daiwa – managing the Singapore Airlines (SIA) IPO.

“In the past, DBS was one of the co-leads, but we managed to convince SIA that DBS should be the lead manager because we had already gained a lot of experience,” recounted Mr Kan.

Over time, DBS served as the lead manager for many foreign listings, which included Australian systems operator Datacraft, Indonesian palm oil producer Kencana and Thai beverage giant ThaiBev.

It was, however, not all smooth sailing. The stock market crash on 19 October 1987, known as Black Monday, resulted in global stock market losses amounting to nearly USD 1.2 trillionin a single day.

For DBS Land, the timing could not have been worse. It had enjoyed a warm reception during September roadshows in London and New York, as well as during its subsequent IPO subscription process in Singapore.

But investor enthusiasm had faded by the time DBS Land made its debut on the SES, 10 days after Black Monday. “The price plunged from the offer price of SGD 1.35 to 85 cents at the closing of the first day of trading. Headache,” recalled Mr Loh Soo Eng, who was then General Manager of DBS Land.

But DBS Land’s strong fundamentals and attractive business outlook still attracted firm commitments of 436 million shares worth SGD 588.6 million from overseas institutions, who “were delighted with the jumbo allotment of 142.5 million shares”, reported The Business Times.

ESA to the rescue

Over the next decade, as the stock market expanded, DBS sought to address industry-wide pain points such as the operational inefficiencies and far-ranging challenges caused by the manual IPO subscription process. One solution that has made history is the Electronic Share Application (ESA).

DBS was the first bank in the world to introduce self-service share applications through ATMs in 1993. Photo: DBS

For retail investors, ESA was a welcome change. It was faster and more convenient to apply for IPO shares via ATMs, eliminating the need to queue at DBS branches to file a manual application form. It was also cheaper: ESA application fees cost SGD 1 compared to about SGD 5 in branches.

For the stockbroking industry, it was a gamechanger.

“ESA was the first time ever in the world that you can actually tap the ATM to allow people to apply and pay for shares. This set the platform for future fundraising in the early 1990s,” explained Mr Kan. “It was a very major development because it solved a very crucial pain point for the bank, for the money market, for the industry, and for individuals, by offering cost savings, convenience, and efficiency.”

DBS conducted ESA trials on smaller transactions and was ready for the mega test: SingTel’s listing in November 1993. About 1.4 million Singaporeans acquired shares, many of whom applied through ATMs.

The success of ESA during the SingTel IPO set a new trend, with more than 90% of subsequent IPO applications executed through ATMs. Eventually, electronic share applications were extended even to secondary fundraising, such as the rights issues or placements of shares, by tapping the ATM network of all the local banks.

Said Mr Kan, “For national interest, DBS shared the concept and the know-how of ESA with the other local banks. It’s for the good of the country that instead of just relying on DBS’ network of ATMs, we could offer ESA via the entire (nation-wide) network, which made it really convenient for investors.”

Singapore as an international financial hub

To fulfil Mr Hon’s broader vision of SES as a capital-raising hub not just for the region but the whole world, DBS recognised early on that it was important to build up Singapore’s role as a financial hub. In particular, the bank was active in pitching to foreign companies to raise capital in Singapore from the early years.

One notable win was Tokyo-based Murata Manufacturing’s listing on the SES in 1976, a year after Hong Kong Land made its debut as the first foreign issue.

Murata’s listing – the first by a Japanese firm – gave rise to a new financial instrument called depository receipts of Singapore (DRS). Issued by DBS, which was the only local manager of the international transaction, the DRS enabled arbitrageurs to buy and sell the same security in different markets to take advantage of the price differences that may exist.

In 1996, rice cracker manufacturer Want Want Holdings chose Singapore, thanks partly to DBS’ strong affiliation with venture capital fund Transpac which introduced the bank to the Taiwanese company.

As more Chinese companies started to expand overseas in the 1990s, Mr Kan and his team started to actively woo Chinese companies to Singapore. Some notable transactions that DBS played a key role in included the listings of China Everbright and shipping giant Cosco on the SES through takeover bids for local counters, as well as the primary listing of pharmaceutical firm Tianjin Zhongxin, which was the first mainland Chinese company to debut as an “S-share” in June 1997.

Over time, an internationally diverse slate of companies has raised capital in Singapore with DBS’ help. These included ThaiBev’s listing in 2006, the largest IPO since SingTel; Sarine Technologies in 2005, the first Israeli firm to list here; and pigments manufacturer Meghmani Organics, the first Indian company to seek a secondary listing here in 2013.

Having served as the lead manager for well over 100 IPOs in Southeast Asia since 2000, DBS has been recognised as the region’s Best Equity House by Alpha Southeast Asia, as well as Best Asia Investment Bank by FinanceAsia.

DBS was also a key player in growing REITs in Singapore, after successfully taking Singapore’s first REIT, CapitaMall Trust, to market in 2002. Singapore has since expanded into a global REIT hub with over 40 S-REITs and property trusts.

While it has never been easy to compete with other financial hubs like Hong Kong, Mr Kan believes Singapore is able to woo foreign listings because of its distinct strengths, particularly its strong reputation as an “open, transparent exchange”.

“It’s very important that we maintain a very solid reputation to attract business, especially in capital markets,” he said.

In a similar vein, DBS leans on its strong reputation and balance sheet, which enable it to withstand market turbulence. “Our financial strength…is important because then we're not under pressure to run for the door when the market turns,” Mr Kan said.

“We will honour our commitment, we will not shirk from it and neither will we sell off shares at the earliest possible moment, just to cut losses. We will do what is appropriate, what is right.”