the-early-years

The Early YearsNation-builder: How DBS took calculated risks to advance Singapore’s industrialisation

By DBS and The Nutgraf, 2 Aug 2023

Riggers at Jurong Shipbuilders Pte Ltd in 1975. Compared to other industries DBS financed, the shipbuilding industry received the largest proportion of financing from the bank that year. Photo: DBS

The articles in this series are presented jointly by DBS and content agency The Nutgraf. In the lead up to the bank’s 55th anniversary, The Nutgraf team interviewed 12 alumni to uncover these lesser-known stories about the bank in its early days, and its key contributions to a young and developing Singapore.

Marching purposefully towards the committee room, the young banker rehearsed his answers in his head. His nerves were jangling, his heart pounding. He was about to come head-to-head with some of the most senior leaders of the bank.

Having just joined the Development Bank of Singapore (now DBS) in 1971, Mr Tan Soo Nan was a fresh-faced young banker as yet unblooded in battle. But he was about to undergo what he called “a baptism of fire”. A committee of senior leaders had gathered to scrutinise his project proposal, and they would give the green light. Or not.

What’s more, he was bereft of modern implements. “In the early 1970s, there was no such thing as PowerPoint,” Mr Tan recalled. “We had to write (the proposal), submit it to the committee, and appear before them.” Armed only with his wits, Mr Tan fielded questions from the committee.

The experience was nerve-wracking, but it existed for good reason. Set up in 1968, DBS was itself a new kid on the banking block, a far cry from the established financial institution it is today. What it lacked in experience, it made up for in thoroughness.

“The committee pooled the perspectives, experiences, and skills of committee members,” said Mr Tan, who would rise to the position of Senior Managing Director over the course of his 29-year career at the bank. “(Operations) were structured so that no one could make a decision to lend or to invest on their own.” Funnelling all proposals through a committee helped the bank manage risk, a concept that lies at the heart of banking.

What “managing risk” meant to the fledgling bank, however, differed slightly from how a commercial bank might define it. Transactions had to go beyond cutting a profit – they also had to benefit Singapore. If a project’s value to Singapore was not clear, Mr Tan said, the committee would ask, “Why are you doing this? Where does it fit in?” The barrage of questions quickly refined Mr Tan’s understanding of what mattered – that success was not always about the bottom line.

Indeed, DBS has been a big part of Singapore’s efforts to industrialise and modernise itself – after all, it was originally named the Development Bank of Singapore. As Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, at the bank’s 50th anniversary, said, “DBS played a crucial role in Singapore’s early industrialisation, taking risks and absorbing downsides to benefit the country but not necessarily the bank itself.”

His words ring true now. But back in 1968, success was hardly a guarantee. Singapore was only a backwater nation, its factories spewing out matches, fish hooks, and mosquito coils. The country had to move upstream or be washed away with the tide, and the clock was ticking.

Of steel and shipyards

Factories were the first order of the drive to industrialise. Not only were they necessary in upgrading the nation’s manufacturing capacity, they also soaked up unemployment which stood at an uncomfortable 7.3% in 1968.

To build factories, however, steel would be required. At the time, NatSteel – known as the National Iron and Steel Mills before it was renamed in 1990 – was Singapore’s only manufacturer of steel, making it an important source of the raw material.

Forecasting that the demand for steel would be on a steady upward trend, Mr Tan and his mentor, Mr Ang Kong Hua, decided to help the steel manufacturer along by attracting investors. Their tool of choice was a convertible bond, which allowed investors to convert their bonds into shares in the company’s stock at a later date.

The typical coupon rate, referring to the interest rate paid by the bond, was around 9% at the time. But Mr Tan and Mr Ang decided to go against the grain. They felt that by including an equity kicker, which would potentially allow bondholders to acquire additional shares of NatSteel’s stock in the future, coupon rates could be pushed lower, to 6%.

“The market did not accept it,” said Mr Tan. He ended up with a shortfall on his hands, one which he had to explain to other big banks who were also part of the transaction.

Mr Tan and Mr Ang stuck to their guns. “We went to the big banks and said, ‘If you are not comfortable because the 6% is too low, we are happy to take your shares. You don’t need to underwrite, so that all of you can be released from your obligation.’” The other banks blinked first. They kept their shares, and the overall transaction yielded a profit.

Beyond profit, Mr Tan and Mr Ang had achieved their goal: to educate the market. After that transaction, lower coupon rates became the market norm. The precedent was set and DBS’ move helped introduce new ideas into the financial ecosystem.

This “catalytic work”, as Mr Tan described it, went on in the shipyards. In 1976, Mr Loh Soo Eng was brought in to help set up a ship financing scheme to fund about 70% of the cost of operating, constructing, or acquiring shipping vessels. Thus far, such a scheme had been noticeably missing in Singapore, even though the nation was located along major maritime trading routes.

“The funding was from the government, but the bank took the risk,” said Mr Loh. Market volatility and other operational risks, for instance, could result in unforeseen financial losses that DBS, not the authorities, would bear responsibility for. He got to work, reaching out to key players in shipping, such as the Singapore Association of Shipbuilders and Repairers, to get them onboard. As the shipping market gradually recovered from the 1973 oil crisis and offshore oil drilling activities started to increase, the scheme was expanded, with DBS continuing to play an active role as both agent and lender.

Small bank, big reputation

As the industrialisation efforts grew, it became clear that success was more than just building more and newer factories and shipyards. To succeed, DBS had to brand the nation as an attractive destination for foreign investment. Strong financial foundation aside, the country needed a little bit of glitz and glamour.

On September 30, 1970, then-Prime Minister Mr Lee Kuan Yew paid a visit to a camera-making factory in Braunschweig, Germany. The factory belonged to Rollei, a German camera manufacturer known for high quality cameras that were all the rage with photography enthusiasts. Mr Lee was a man on a mission: he wanted Rollei to shift their production lines to Singapore.

He succeeded in convincing them. In 1971, the first Rollei factory opened on Alexandra Road. It was a significant event in more ways than one. Not only did Rollei’s entry bring German expertise and upstream capabilities, such as precision manufacturing, to Singapore, all Rollei cameras going out into the world would have the Made in Singapore stamp.

It catapulted the nation onto the world stage. One Rollei 35 S model assembled locally – and subsequently gold-plated – even found its way into Buckingham Palace when it was gifted to Queen Elizabeth during her visit to the city-state in 1972.

President Benjamin Sheares presenting gifts to Queen Elizabeth II that included three gold-plated Rollei 35 cameras in 1972. Photo: National Archives of Singapore

The magnitude of the undertaking was not lost on DBS, which helped to finance the company’s entry despite being a newly formed bank. A small fry, as it were. “There was almost no security if Rollei had collapsed, except the physical factories that our money was used to build. But the factories weren’t worth so much,” recalled Mr Ang, who had been part of the team that brought Rollei to Singapore. Rollei was eventually pushed out of the market by the Japanese, but its legacy in Singapore was already in place.

“Singaporeans know DBS as the modern new bank,” said Mr Nawaz Vilcassim, who had been secretary at the Rollei Group of Companies prior to joining DBS. “But there was more to it. DBS played a key role in building up the image of Singapore. How do I know that? Because I was on the other side with Rollei.”

Purpose is twofold

The bank’s initial raison d'etre was to develop Singapore into an industrialised nation. But that didn’t always gel with the original purpose of any private company, which is to turn a profit. This tension between private profit and the greater good is one that DBS has had to manage over the years, said senior executives at the bank.

Mr Loh, for instance, recalled a meeting with an irate customer many years ago when he was still a junior officer. The businessman was seated in a meeting room with Mr Loh and his boss, and the heated conversation was taking an ugly turn.

In the face of adversity, the determined businessman found himself at a crossroads. Having received a notice from the government advising relocation of his sand processing company in Tampines compelled him to seek greener pastures. His quest led him to a promising 25-acre site in Punggol, where he saw immense potential.

Undeterred by the challenges, he invested SGD 1.25 million in the land, while managing the operations in Tampines. However, his hopes were crushed when the government announced the acquisition of the Punggol site. The burden of repayment loomed over him as he owed the bank SGD 800,000 for his business financing. In the land-scarce nation of Singapore, rules prevailed, leaving him with no choice but to honor his debt.

Recalled Mr Loh, “The businessman told my boss, ‘Manager Lau, you have a 50-storey building here. You go up and bring the key and I’ll go with you to the top floor. You open the window, I jump. Case closed.’”

For DBS, the wellbeing of clients was a purpose in its own right. Toeing the line was a precarious business, but the bank decided to stick its neck out and help its client.

“We calmed him down and talked to him,” said Mr Loh. “And we extended the deadline of his recall letter.” The bank also rendered assistance while the besieged businessman set up a new company, and stayed with him while he appealed to the government for compensation.

“The final offer from the government was SGD 630,000 in compensation,” said Mr Loh, adding that the process took more than a year. “By then, the new company was doing well and he was able to redeem the overdraft. It shows that DBS is not just a fair-weather bank. Whether the loan amount is small or big, we do care for our customers.”

Power to the little ones

From NatSteel to Rollei, tales of DBS’ brushes with the likes of domestic and international giants are well-documented. But as Singapore industrialised, it was not only corporations that were in need of the bank: small businesses were, too.

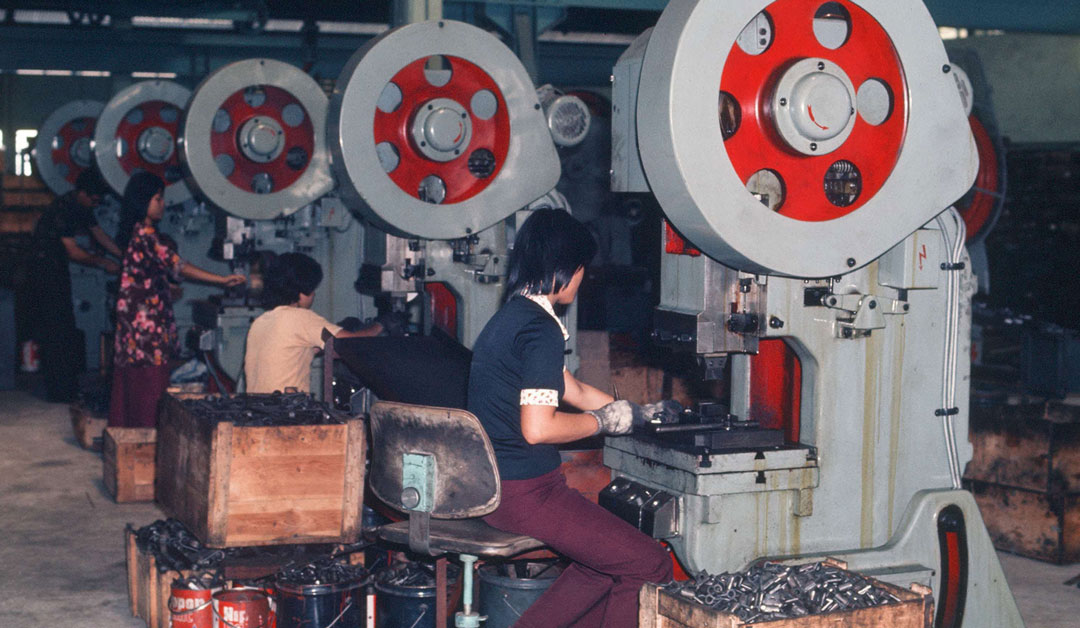

DBS financed many local enterprises, among them Yong Tai Loong Pte Ltd in the 1970s, manufacturers of aluminium fixtures for the home and office. Photo: DBS

Small family-run firms were commonplace in Singapore during the early post-independence years. They were the small-and-medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), or “backyard operators”. As Singapore sought to industrialise, the Jurong Town Corporation – set up the same year as DBS to manage Singapore’s industrial estates – encouraged these SMEs to shift to proper locations in designated areas.

“These businesses were very manual in their operations and manufacturing processes,” said Ms Lim Sok Hia, who joined the bank in 1979 as a trainee. “They had no strong accounting or record-keeping capabilities.” For that reason, such SMEs usually faced hurdles when it came to obtaining financing to upgrade or scale their businesses.

The risk for the bank had to be carefully assessed when it came to helping these companies. In 1976, three years before Ms Lim joined, it was decided that the financial hazards were worth it. The Small Industries Financing Scheme started that same year, and by 1978, 63 local companies were given loans totalling SGD 9.7 million.

The scheme offered equipment financing to SMEs to help them modernise their tools of trade. “The other local banks were not keen because if the company failed, they would get scraps,” said Ms Lim, who retired in 2005 as Managing Director and Head of Corporate Credit. “We administered the loans, but it did not come free. There was risk-sharing – at one stage it was 50-50. The bank had to take that risk.”

Beyond helping small businesses upgrade, the bank also imparted to them skills such as meticulous record-keeping – crucial to ensure legal and regulatory compliance in a modern world where things were becoming increasingly structured.

Was it lucrative? “Not at all,” said Ms Lim. “But we felt it was necessary… We were not looking at the asset when we made the decision to lend. We had to be convinced on the business proposition, their business viability going forward. We were there to support and guide them, to enable them to take off and transform.”

From fashioning Made in Singapore cameras to fashioning a nation out of steel, the growth of the bank, especially in its nascent years, mirrored the growth of a nation. Both got to where they are today not by playing it safe. They took risks – not just on projects, but on people, and above all, where it mattered.