- Banking

- Wealth

- Privileges

- NRI Banking

- Treasures Private Client

- The JPY is now highly under-valued compared to its fair value implied by the DEER model

- Such a misalignment should narrow over time, given the trade implications of an undervalued JPY

- We found that Japan's net export volume growth is positively correlated to JPY under-valuation

- Net export volume growth is positively related to FX under-valuation for other major economies too

- Misalignments from our DEER fair values thus cannot be sustained for the JPY, and other currencies

Related Insights

Extreme JPY weakness relative to history

USD/JPY has climbed above 130 last week, after the BoJ reaffirmed its Yield Curve Control target of 0% for the 10Y JGB. We consider implications of current JPY depreciation for its DEER valuation, and the impact on Japanese trade.

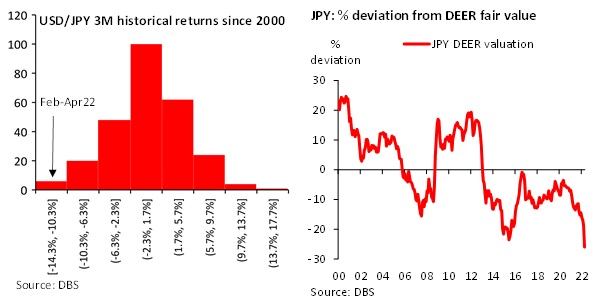

For context, the JPY has been weakening against the USD over the last three months, amid expectations of policy divergence (see DBS Flash: The Yen’s impact on the DEER strategy, 30 Mar 2022). The loss last week brings the decline to an extreme, with the JPY/USD 3M return coming to -13%—a return rarely seen across the distribution of historical returns since 2000. Our DEER strategy, which seeks exposure to undervalued currencies, has a long position in the JPY, and recent moves imply that the JPY’s undervaluation is even starker today.

From the perspective of our DEER fair value, the JPY clearly stands at its cheapest since analysis started in 2000. Historically, when the JPY traded at such low valuations, such as in 2015, it has managed to strengthen and revert to more neutral levels. There is reason to expect JPY recovery to recur going forward, with mean reversion driven by the changes in trade activity arising from such exchange rate misalignments. Fundamentally, while currencies can fluctuate widely, they cannot deviate too far against fair values. Any extended deviations will result in wider and wider trade imbalances, which are unsustainable in the long run.

During the JPY’s recent selloff, there has been frequent commentary that a weak JPY policy is perhaps misguided, or even economically detrimental. The reason given is that Japanese companies have been outsourcing production in recent years, and will benefit less from a weak JPY. Such speculation provides an impetus to examine the relationship between the JPY and Japanese exports/imports volumes over the years. Could we still expect a traditional trade boost from the weaker JPY for misalignments to close?

Establishing the link between FX and trade

To lay the ground for our own analysis, we first provide an overview of international trade theory and existing literature on trade and currencies.

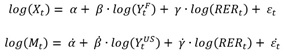

Whether a currency devaluation improves the trade balance depends on the well-known Marshall-Lerner condition, namely that the sum of absolute import and export price elasticities are greater than one. Modern estimation of export and import price elasticities follow the reduced-form model proposed by Houthakker and Magee (1969), with real exports linked to relative export prices and trading partners’ GNP, while real imports are linked to relative import prices and domestic GNP. With purchasing power parity, the relative price ratios also represent the long run exchange rates. It is thus common to replace relative prices with real exchange rates in estimation. For instance, Bahami-Oskoee and Brooks (1999) found the elasticities of US bilateral trade with six trading partners using bilateral real exchange rates, based on a cointegrating relationship of the following form:

Despite its theoretical importance, Bahmani, Harvey and Hegerty (2013) assess that there is no strong empirical evidence supporting the Marshall-Lerner condition. They believe that the cointegrating relationships between exports/imports and other economic variables could have been mis-specified, resulting in inaccurate estimates across the literature. Indeed, trade relationships had become ever more complex since the 1990s due to the rise of global value chains. Given a greater proportion of intermediate goods imports for processing into final exports, traditional trade equations may be missing these features.

Focussing on growth and J-curve dynamics

To circumvent this problem and minimize the risk of spurious regressions, we propose modelling export and import growth rather than levels, as is traditionally done. There are two reasons why such analysis is more amenable. First, unlike modelling of exchange rate levels, information on the levels of exports and imports is not as important as compared to growth rates, and they can be dropped with little loss of meaning. Second, J-curve dynamics, where a trade balance initially deteriorate upon a devaluation before improving beyond its starting level, are implied in a straightforward way if we find persistent changes in export and import volume growth arising from currency misalignments. This is because net export volumes will always improve if export volume growth rise and import volume growth fall, while any currency shifts away from fair value (and nominal price changes) are one-off.

For our case, a larger undervaluation of the JPY should imply export volume growth that is higher than average, and import growth that is lower than average. We thus propose estimating the sensitivity of Japanese export and import volume growth vis-a-vis the JPY’s DEER valuation based on the following functional form:

Xt and Mt are Japan’s real exports and real imports in quarter t, gFt is the trade-weighted y/y real GDP growth of Japan’s trading partners in quarter t, gJPt is Japan’s y/y real GDP growth in quarter t, and DEERt-i is the average JPY DEER valuation for quarter (t – i). DEER valuations are deviations from long-term fair values and are stationary (see DBS Focus: Currency fair values: What’s cheap and what’s DEER?, 8 Jan 2020). We perform OLS regressions on quarterly data from 2001 to 2021.

As currency misalignments can take a period of time to fully influence export and import volume due to contractual rigidities, we estimate the impact of DEER misalignments on export (or import) growth to be the sum of four coefficients, for the current quarter and the past three quarters.

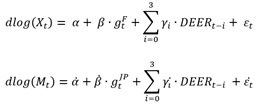

Assessing Japan’s trade sensitivity to the JPY

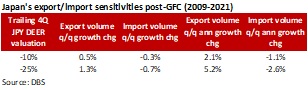

Our analysis found that when the JPY is undervalued by 10% on average over the last 4 quarters, then Japan’s export volume growth is boosted by 0.1% q/q (0.4% annualised), and import volume growth is compressed by 0.3% q/q (1.1% annualised.). The overall impact on net export volume growth is seemingly small, but the economic impact could be meaningful given the large proportion of trade relative to GDP, and low long-term growth rate of Japan. With the JPY now around 25% lower than its fair value, we estimate that the net exports’ boost to growth can reach a sizeable 0.7% per annum.

Recent data after the 08/09 GFC also suggest that Japan’s export sensitivity to currency misalignments has grown, while the impact on import growth is little changed. Misgivings about the efficacy of a weak JPY are thus misplaced. Our analysis of the data found no reason to challenge the BoJ’s view that a weak JPY is generally positive for the economy, at least from the trade perspective. That said, policy may have broader considerations beyond trade competitiveness, and exchange rate uncertainty and volatility itself may well pose an economic drag that demands policy attention.

Trade sensitivities to DEER for other countries

With just 80 quarterly observations, it is not possible to show that our estimated export volume and import volume growth sensitivities are statistically significant. Still, the central estimates support the case of an undervalued JPY spurring net exports growth, which is not unexpected with Japan being an export and manufacturing-oriented economy. Could other economies also see a similar trade impact from currency misalignments indicated by the DEER?

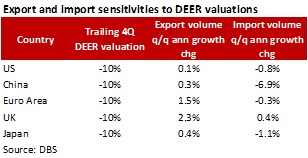

To affirm that the trade impact of our DEER misalignments is realized in general and not just for Japan, we extend our trade sensitivity analysis to the US, China, Euro Area, and the UK, using the same model specification. Individual country regressions across the 2001-2021 period showed that the coefficients were as expected for all 5 major economies, except the UK. Nevertheless, the larger sensitivity of export growth relative to import growth suggests that any GBP undervaluation will still boost net exports. We table the country sensitivity estimates below:

Only China’s import sensitivity is found to be statistically significant (based on an F-test). Still, the mostly consistent signs across export and import sensitivities suggest that a large-scale panel regression of more countries could yield a statistically significant result.

Trade-driven reversion to FX fair values

In conclusion, we have shown that the JPY’s current sharp undervaluation will have a trade and economic impact over time. This implies that its misalignment from our DEER fair values is not sustainable, and some strengthening is expected over time. We have also shown this to be the case in general for other major economies. A consistent strategy through extreme periods of valuations overshoot or undershoot should eventually pay off.

To read the full report, click here to Download the PDF.

Topic

The information herein is published by DBS Bank Ltd and/or DBS Bank (Hong Kong) Limited (each and/or collectively, the “Company”). This report is intended for “Accredited Investors” and “Institutional Investors” (defined under the Financial Advisers Act and Securities and Futures Act of Singapore, and their subsidiary legislation), as well as “Professional Investors” (defined under the Securities and Futures Ordinance of Hong Kong) only. It is based on information obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but the Company does not make any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy, completeness, timeliness or correctness for any particular purpose. Opinions expressed are subject to change without notice. This research is prepared for general circulation. Any recommendation contained herein does not have regard to the specific investment objectives, financial situation and the particular needs of any specific addressee. The information herein is published for the information of addressees only and is not to be taken in substitution for the exercise of judgement by addressees, who should obtain separate legal or financial advice. The Company, or any of its related companies or any individuals connected with the group accepts no liability for any direct, special, indirect, consequential, incidental damages or any other loss or damages of any kind arising from any use of the information herein (including any error, omission or misstatement herein, negligent or otherwise) or further communication thereof, even if the Company or any other person has been advised of the possibility thereof. The information herein is not to be construed as an offer or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities, futures, options or other financial instruments or to provide any investment advice or services. The Company and its associates, their directors, officers and/or employees may have positions or other interests in, and may effect transactions in securities mentioned herein and may also perform or seek to perform broking, investment banking and other banking or financial services for these companies. The information herein is not directed to, or intended for distribution to or use by, any person or entity that is a citizen or resident of or located in any locality, state, country, or other jurisdiction (including but not limited to citizens or residents of the United States of America) where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation. The information is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy any security in any jurisdiction (including but not limited to the United States of America) where such an offer or solicitation would be contrary to law or regulation.

This report is distributed in Singapore by DBS Bank Ltd (Company Regn. No. 196800306E) which is Exempt Financial Advisers as defined in the Financial Advisers Act and regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. DBS Bank Ltd may distribute reports produced by its respective foreign entities, affiliates or other foreign research houses pursuant to an arrangement under Regulation 32C of the Financial Advisers Regulations. Singapore recipients should contact DBS Bank Ltd at 65-6878-8888 for matters arising from, or in connection with the report.

DBS Bank Ltd., 12 Marina Boulevard, Marina Bay Financial Centre Tower 3, Singapore 018982. Tel: 65-6878-8888. Company Registration No. 196800306E.

DBS Bank Ltd., Hong Kong Branch, a company incorporated in Singapore with limited liability. 18th Floor, The Center, 99 Queen’s Road Central, Central, Hong Kong SAR.

DBS Bank (Hong Kong) Limited, a company incorporated in Hong Kong with limited liability. 13th Floor One Island East, 18 Westlands Road, Quarry Bay, Hong Kong SAR

Virtual currencies are highly speculative digital "virtual commodities", and are not currencies. It is not a financial product approved by the Taiwan Financial Supervisory Commission, and the safeguards of the existing investor protection regime does not apply. The prices of virtual currencies may fluctuate greatly, and the investment risk is high. Before engaging in such transactions, the investor should carefully assess the risks, and seek its own independent advice.